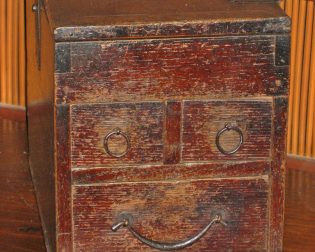

Meiji-era Japan soaked up the ideas of the West like a sponge and plunged headlong into modernization. In the midst of industrialization, the craftsman who turned out handmade furnishings was marginalized.

Meiji-era Japan soaked up the ideas of the West like a sponge and plunged headlong into modernization. In the midst of industrialization, the craftsman who turned out handmade furnishings was marginalized.

For tansu, the Taisho (1912-1926) and Showa (1926-1989) eras represent, beyond anything else, economy and efficiency.

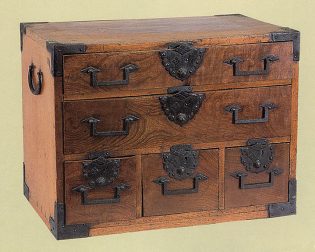

Tansu represent an interesting commingling of trades in Japan during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Cabinet makers, or joiners, worked intimately with lacquersmiths and hardware blacksmiths to make the chests and cupboards of a society in the throes of economic expansion. Much like the joiners, and blacksmiths of colonial New England, the combined efforts of these tansu craftsmen reflected a growing commerce and trade specialization.

Several conditions were necessary for the evolution of the common cabinetmaker: the three trades associated with tansu finding themselves in close proximity, a clientele in need of storage cabinets and with the means to pay for them, and a reliable supply of wooden boards. The first two conditions were met by the growth of urban environments from the late sixteenth century forward.

The growth of towns, especially castle towns, in concert with the removal of samurai from the countryside created thriving local economies.

The growth of towns, especially castle towns, in concert with the removal of samurai from the countryside created thriving local economies.

Craftsmen making tansu continue to exist in Japan today. Like many trades, it has undergone changes wrought by machinery and mass-consumer culture. It is the designer-craftsman rather than large cabinet shops who best characterize the traditions inherent in Edo- and Meiji-era tansu. The influence of tansu, both as design and furnishings, continues to spread beyond Japan’s shores.

Perhaps the greatest sign of this influence is seen in the interest American craftsmen have had in Japanese woodworking over the past twenty-five years. Japanese toolmakers now enjoy the patronage of American woodworkers, and cabinetmakers from California to Illinois to Maryland have built furniture inspired by tansu.